How I Met My Father Long After He Died

The meditations of the heart challenged by those wondering why I lionize a father who caused more than his share of pain - not a perspective for the faint of heart.

I have written about my father more times than I can count since 2021, when I was unexpectedly launched into a political journey that continues to this day (I document those adventures at and insights over at Captain K’s Corner). Most of the time, I’m discussing high points and key things that the old man shared with me in the quarter-century we crossed paths here on Earth. I’ve posted several letters, or excerpts of letters, highlighting his razor-sharp wit and bluntness, like this one, which I received in my first week upon arriving in Afghanistan:

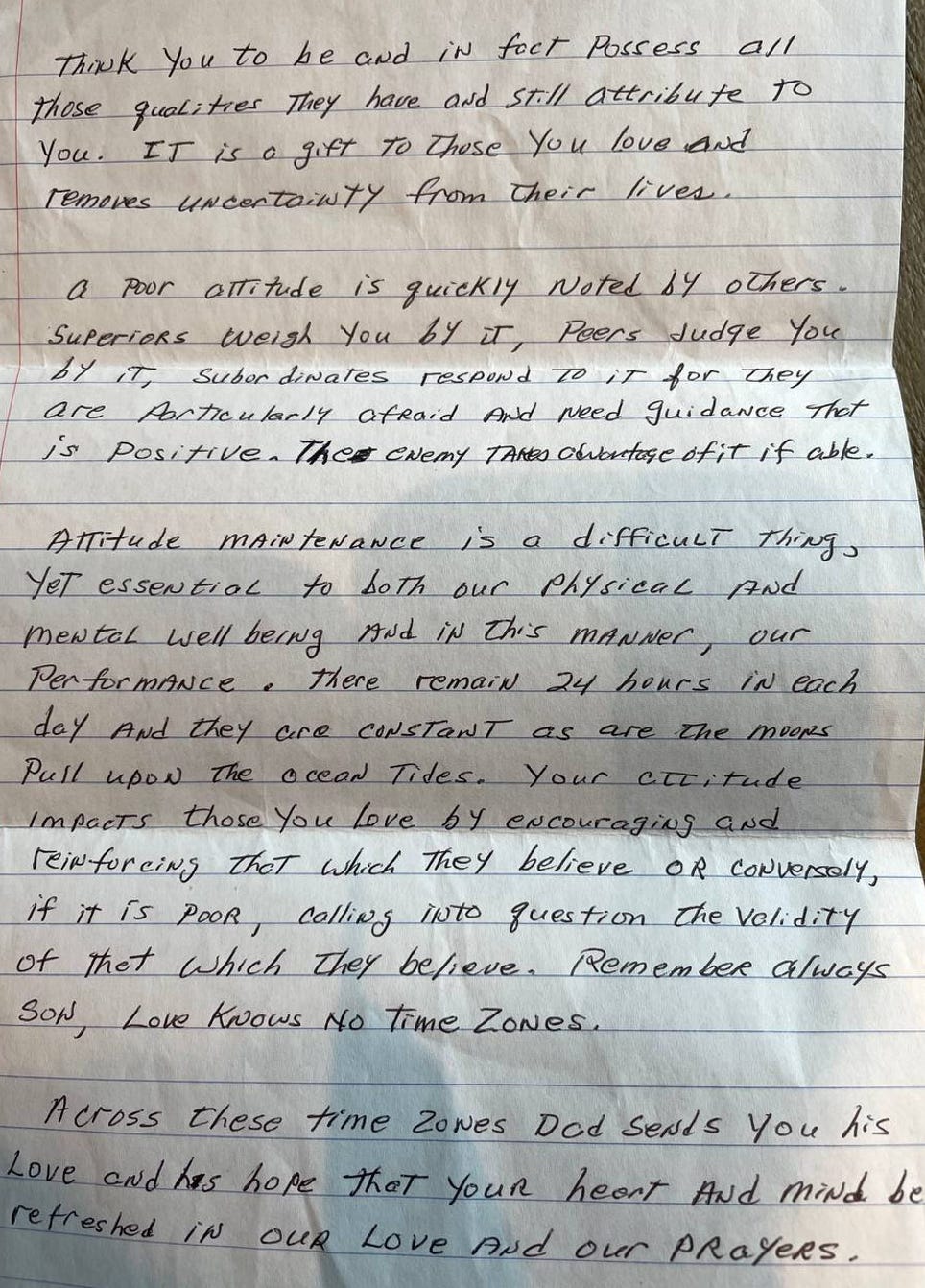

That summer was his last one here, because he was dying of pancreatic cancer when I got my orders to go overseas. There were a few long weekend passes granted by my commander, then a stretch of block leave back home before the deployment, and that was that. All I had left were my letters. They continued to trickle in over the last two months of his life, like this masterpiece on maintaining a positive attitude:

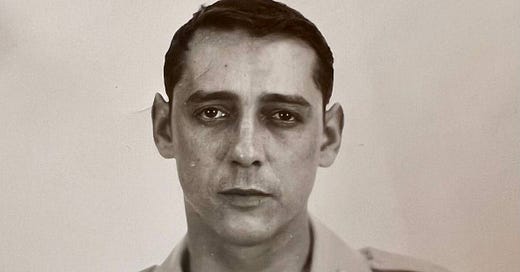

I was 25 when I went storming out of those doors in Mississippi, where I grew up. I’m recollecting those feelings at 40 today. Up until that morning, the most emotional thing I’d ever struggled to process was watching my childhood dog get put to sleep when I was 18; on this day, however, I prepared to say goodbye for the last time, realizing full well that my father’s choice for palliative care only meant time was running out. I was a First Lieutenant in the Army at the time, and the only thing I could think to do as I approached dad’s chair was to pop to attention and render a salute. At his peak, Dad was over 6’2” with a dark complexion and sharp appearance in uniform. Disease had withered the colonel down to perhaps 110 pounds, so the last thing I expected to see was him popping up out of that chair like he was 30 and to return that salute as crisply as the day he first learned to execute one.

Dad died on September 7, 2010. I was authorized emergency leave to attend his memorial service at home, though I couldn’t get back for his interment at Arlington National Cemetery in January 2011. That’s where I go see him these days, and time has done nothing to take away the sting and emotional shock value of when I turn the corner to his spot in the columbarium.

My mother doesn’t understand the admiration I have for my father. I’ve lionized him publicly to a large following, choosing to focus on the exemplary traits that made me who I am rather than focusing on negative behaviors and patterns of conduct that have likewise plagued me from time to time as I’ve grown older. I would argue that my deep-seated appreciation for my father comes from the fact that I’ve come to know him so much more after his death than I knew him when he was alive. That is the gift that comes with experiences both good and bad, if you choose to receive all those lessons and learn from what they offer.

One reason I love championing and supporting veterans is because I’m the son of one who served three tours in the jungles of Vietnam, including in some of the worst years of the war, and the brother of two Army helicopter pilots, one of whom is one of the most decorated aviators in the history of Army Aviation. I would feel a deep urge to support veteran causes even if I were not one myself. Of the three of us who have served in combat, Dad had it the worst of all serving in the infantry in a chaotic, traumatizing, and unwinnable conflict, followed by my brother, who flew in the highly kinetic days of the Iraq War, when Saddam still had conventional forces spread throughout the country. I was an intelligence officer serving on battalion staff when deployed and not engaged in direct combat – and even I still have my own issues associated with the stress of being locked into a gravely serious disposition for a year.

Dad once told me, in a moment of lucidity, that he engaged in thrill-seeking behavior because he struggled to replace the thrill that came with kill or be killed he grew so addicted to in Vietnam. In those days, soldiers (especially officers) were discouraged from seeking mental healthcare or counseling. The stigma associated with doing so led them to believe they’d be pushed out of the service or ridiculed, so in most cases, they didn’t go. They nursed themselves in other ways – like with gambling, alcohol, and women. Growing up, I grew frustrated with Dad zipping out of the driveway on a Saturday morning to spend all day at the American Legion. I didn’t realize then that he was trying to drown out the demons of his past, which he was hesitant to share with me, the youngest of his children and the only one born in his second marriage.

Both of my parents smoked like chimneys and I was often picked on in school for smelling like an ash tray, even though I couldn’t tell because my nose was accustomed to the world around it. Those early years were filled with some interesting interactions, like when Dad told our neighbor, a Baptist preacher, that he would stay out of his church as long as the preacher stayed out of his bar. He never liked being evangelized or prodded to go to church, although he died a man who believed in Christ and salvation. Early on, I demonstrated a knack for good grades without having to put in much effort. That pleased Dad.

He was happy with those grades until the first A minuses started trickling in and receiving the “what happened here?” treatment. Those turned to B pluses over the years, and then once, in 11th grade, a C in Trigonometry. More on the grades later. As I got a little older, Dad and I grew to love baseball thanks to a family trip to Atlanta in 1993. Soon, nearly all our vacations involved baseball stadiums, and naturally, I wanted to try my hand at the game myself.

Unfortunately, I was horrible at the game I loved. Foul balls prior to striking out were events I welcomed with gladness, and an inadvertent fair ball was something to puff my chest out over. I just wasn’t an athlete when I was young and had very poor coordination due to lots of inner ear troubles that plague me to this day. My folks continued to drag me to practice and games up until I reached an age that required making the team – and my high school was a nationally ranked powerhouse. My days suiting up on the diamond ended at 15, a year or so after Dad described to me in vivid detail how embarrassing it was to watch me suck so badly at baseball despite being such a big kid.

For most of my life, probably until my early 30s, I suffered from low self-esteem. I’ve come to realize most of those issues stem from what I grew to believe about myself, and what I was capable of. I knew nothing of hard work, fitness, or nutrition – I just ate what was in front of me and suffered the consequences of poor athletic performance and being made fun of by kids at school – and Dad at home. One day we were on the patio, and he made such demeaning comments about my appearance that I began depriving myself of treats and using the single piece of cardio equipment we had because I became obsessed with proving the old man wrong. What he said was hurtful and something I would never recommend a father to say to a kid struggling with image – but for me, it lit a fire to stop accepting less from myself and provided incentive to demand more.

The brain people know me for today was always there, full of activity, trivia, minutiae, and on-the-fly calculations. The demeanor and wit were not with me until I was on my own, and even then, it took some time. I would credit Army ROTC and the military for making me into someone with a serious edge that people didn’t shrug off as a wonk. My grades were good to start college, and eventually I became so immersed with working with the Ole Miss baseball program that I let my grades slip. I had three rough semesters back-to-back-to-back that finally pushed Dad over the edge and into the realm of no longer caring what kind of grades I brought in – three straight semesters with GPAs in the mid-2s will do that. In a low and regretful moment early in college, Dad and I wound up scuffling on the kitchen floor because he had struck me across the face over grades. Being unable to please Dad made me no longer invest heavily in academic success.

I spent the summer of 2006 expecting to be put to work by a scout for the Florida (now Miami) Marlins in what is called a “bird dog” role. Unpaid, but you run around with a radar gun and notepad looking for talent in the bushes and trees and report back if you find anything. Baseball is filled with legends of all-time greats found skipping stones off a lake with such velocity it foretold a career hurling ferocious fastballs. That call never came. Realizing there was almost no chance of having a meaningful career in professional baseball without real playing experience and having little interest in my now-stagnant business degree, I decided to contract with the Army ROTC. I was interested in the Air Force ROTC the semester prior but faced a serious uphill climb with their strict medical requirements and wasn’t willing to quit the baseball program as they requested, so I backed out.

The Army, however, needed bodies to plunge into two unwinnable conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and my personal belief system hadn’t yet matured to the point in which I could see those quagmires for what they are – unjust, unwinnable, and not worth sending men and women to die over. The family branch had a waiver for me almost as soon as the ink dried on my application and was willing to take me on even if I was on the fast track to be deaf in one ear as I am today. Then, an amazing thing happened as if some great light in the universe had been turned on…

My father became proud of me.

I am thankful for my military service and understand the lessons learned and the critical insight my time in uniform provided for me to make it in the cruel world I operate in today. Those lessons cannot be found anywhere else other than leading men in conflict and meeting standards that would kill most untrained men. In recent years, I’ve come to question if I joined the military for altruistic reasons, or if it was because I wanted to finally mean something to my father.

My own failures as an adult have reconciled a truth to me – that my father always loved me and was proud of me, but he simply couldn’t show it all the time. He lacked the ability and emotional clarity to do so because he was so scarred from trauma. Two of my siblings give me a hard time to this day because I didn’t get smacked around by a younger version of Dad like they did, as they ducked behind the driver’s seat to avoid his grasp and swift backhand. They argue that my mother prevented this from happening. Abuse is one thing, but standards are another. I regret deeply not having strict standards for excellence as a young kid, with both of my parents working, but thanks to perhaps a miracle, have found them for myself.

When I started wearing that camouflage uniform, something changed in the old man.

Regular text messages would float in with words of encouragement. Visits from my friends, like future Marine Corps officer Preston, would turn into combat stories stretching into the wee hours of the mornings. Dad painted a vivid picture of what life in the military would be like for both of us, and with stunning accuracy portrayed the world for almost exactly what it has become nearly two full decades later. In those later years of his, I found a stunning connection to him – almost as if I had picked up a book that had been at rest on a shelf for 21 years and suddenly realized it was the greatest one I owned.

It shouldn’t have taken suiting up in uniform and giving Dad a chance to live vicariously through yet another child for him to be proud of me, but I am glad that it happened, and I wouldn’t change it if given the opportunity. It allowed me to begin to know the earthly father I had, and to begin the postmortem process of putting the pieces together after he died that hinged on my own life experiences drawing me closer to him.

“Do as I say, not as I do,” he would often say. He knew his beliefs were stronger than his ability to act on his beliefs, or to be consistent in them. Now I understand it. The harsh, critical voice that permeated my childhood gradually shifted into a voice of wise counsel. This couldn’t have been more obvious to me than when I reported to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in June 2008 for my first days on Active Duty as a newly commissioned officer. There had been a major disconnect between the Army ROTC Cadet Command and the big Army, the one I reported to, in which my waiver for severe hearing loss no longer covered the service’s evaluation standards. They funneled every lieutenant into a vision and hearing screening booth in that first week and found my hearing severely lacking. It was a permanent grade 3 of 4 profile, requiring me to be evaluated by a medical retention board. My commander, given my lack of experience in service, recommended I be separated and sent back to civilian life rather than impose a burden upon the service. Who was it that had my back?

Now 65 years old and semi-retired from post-military work, Dad drove out to Oklahoma and testified before that board – featuring a colonel, three lieutenant colonels, and a major, who was the doctor of the group. When I finally appeared before the board, the senior officer made it clear to me that “despite his inclinations” (and his do not retain vote), three of the other board members voted to retain me and switch me from the Field Artillery branch to Military Intelligence. The old man congratulated me and immediately jumped in his car and drove back home. This set the wheels of my adult life in motion, and I’ll never forget who it was who jumped in front of that bullet threatening my military career.

In those last two years of his life, Dad was a regular visitor to wherever it was I was stationed. He came to see me when I was in training at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, around Christmas 2008, then made several visits to my first duty station at Fort Hood, Texas. He was there for me, right before he got his cancer diagnosis, when I got married the first time around. In one particularly gripping moment, Dad passed on to me one of the greatest lessons a man could ever hope to receive:

In Fall 2009, I came out on the promotion list to move up to First Lieutenant, along with thousands of my peers in what amounts to a near-automatic promotion. The only way a Second Lieutenant misses that promotion is by being out of physical fitness standards, or by having severe problems with the law or military justice system. Modern lieutenants play the jump from the gold bar to the silver one down as much as possible, so I went along with it and told Dad he didn’t need to bother coming out to Fort Hood, eight hours each way, to see the eventual promotion ceremony. What I didn’t know at the time is that cancer was beginning to eat away at Dad – I had figured perhaps he could come watch me get promoted to Captain some eighteen months later.

The sun rose on November 30, 2009, and with it, brought Dad to Fort Hood one last time. He attended the promotion ceremony with my brother, David, the decorated Apache pilot, whose former commander and family friend would be pinning my new rank insignia on my uniform. Dad congratulated me once again, and I tried to shrug off the significance of what I believed to be an automatic promotion. What he said remains plugged into my mind to this day, and surely will as long as I live:

Son, I served with a lot of Second Lieutenants in Vietnam that didn’t live long enough to make First Lieutenant.

With that, the lesson – never fail to appreciate the small things. They are never guaranteed. I never knew this was Dad’s last promotion ceremony. I wound up celebrating my next promotion on a 110-degree concrete pad in June 2011, after returning from Afghanistan, with a small formation of soldiers, one of my best friends, and my ex-wife present. Dad was sorely missed.

Memories like that, though they sting like a sunburn, jar others to life. Like that time in 2001, when the towers fell and 16-year-old me was afraid to travel to the Northeast that November for a youth leadership conference I had been selected to attend over all my peers. I did everything I could to sway my Dad to move along with letting me back out of the summit. What I got instead was:

Son, I didn’t serve three f***ing tours in Vietnam for my son to be afraid of a bunch of stone-age, camel herding savages.

Guess who got on the plane that November? You bet – I wasn’t going to let the old man down. You see, the brilliance was always underneath the rough veneer, and like the mountain sun, came out from behind the clouds from time to time. Dad had guts, and those guts are what he wanted to pass on to me and were the reason why he always demanded so much out of me, even if I wouldn’t always agree with the way he expressed those desires.

For ten years after he died, the memory of my father slept within me. He was a flawed man, I thought, and I struggled at times to forgive his demanding nature and cutting taunts. I had a hard time moving on from some of the things the vodka forced him to say, or some of the aggressive moments I witnessed under the roof of our home growing up. I wanted a perfect father to remember. I visited his grave in Arlington in 2011 upon my return from Afghanistan, then again in 2017 and 2018 when I was in Washington for business. Only three times in that decade in which all three of my children were born did I visit my father. Time had driven us apart as the leaves withered, sun scorched, and seasons changed on those hallowed grounds upon which he rests.

I left the active military in December 2013, no longer willing to serve in an Army hellbent on returning its troops to unjust and unwinnable wars one deployment after another, and looking to provide stability to family life, which was already troubled. I hung up the uniform for good in 2014 after six unfulfilling months in the Army Reserve. I labored away at jobs, not callings, skipping between industries in Texas in a period in which I was laid off twice and quit a terrible job with no prospect of receiving unemployment. I was a full-fledged participant of the rat race, even though I did have one job that fully used my skills and abilities that helped prepare me for today, rising early in the morning and getting home at dusk trying to live the so-called American Dream.

The dystopian 2020 year changed my life forever, particularly regarding the events surrounding the 2020 election and the influence I was charged with beginning in 2021. That year, 2021, was the year in which my life fell apart when everyone in my sphere of influence thought I was on top of the world. I entered that year married with three kids. I closed that year in the process of becoming a single man, with very little time to spend with my kids. It was in these growing pains, these times of tremendous darkness, that I reconnected with the man I had only begun to know before he left me. In those sad days, I would spend time pouring over his letters to me, taking in his wisdom and love deep into my heart. It turns out, I was a lot more like my Dad than I thought I was.

I’ve been jabbed at by family members for years for being religious. I didn’t come from a church-going family but grew up attending a private Christian school in which I was exposed to teaching which I believe to be spiritual truths. I’ve considered myself to be a Christian since I was 17 years old. Like anything else, the process of spiritual maturity is an ongoing thing that takes place all the way until physical death. It spans ups and downs, peaks and valleys, victories and failures. If you don’t believe me, read the stories of King David and report back. God is the one who makes great things from broken vessels.

Still, my beliefs and youthful naivete led me to think I was immune to certain things. Surely, I wouldn’t do thisor that, fall further than I’ve ever fallen before, or become a divorced person, even though my former marriage was a competitive struggle from the words “I do.” Clearly, because I believed in God, I wouldn’t wind up like 50% of those who get married or do anything I would have scoffed at others for doing, right?

Likewise, Dad didn’t set out one day with a goal of carrying out the negative or dishonorable things he wound up doing. They were the natural manifestations of trauma responses that led him to inflict the wounds he did on the people he loved. When I was young, I took those things personally and couldn’t see the man within. I only saw the angry, brooding Dad who got goofy when he drank vodka, and mean when he drank rum. My older siblings had it way worse when Vietnam was much fresher. When Dad was young, one of my brothers lost a pair of brand-new mud boots in a Pennsylvania creek bed, and it was all his siblings could do to keep him from being sucked into this sinkhole and drowning. They got back to their grandparents’ house, where they were visiting, and - no boots. A beating so bad ensued it had to be broken up by direct family intervention.

I was spared most of these physical accountings because I had a different mother and because Dad was older and had mellowed out a bit. Part of me wishes I suffered them, because I still take so much heat from my brothers about not having it as bad as they did, and it is because I subjected myself to my own challenges that I wound up getting off the pathway to becoming a soft man with no heart to push myself above and beyond predetermined limits and tolerances. Dad’s scars left marks, but I’ve left my own.

I’ve spent most of the past 15 years since I lost my father surrounded by two camps: those who loved him but choose to remember the funny jokes or serious life lessons from a comfortable distance, and by bitter souls who choose only to remember him for his negative characteristics, caused by trauma and suffering, and hurtful actions. I have learned to see the greatness of the man through all of who he was and continues to be as I live my life – going all the way into the worst, darkest memories of our lives to retrieve the lessons. I went into marriage with the best of intentions and failed. I wasn’t ready, didn’t start off right, didn’t handle conflict right, and created a pathway for a miserable coexistence. Toward the end of the marriage, I excused myself to behave in a way I don’t condone, betrayed the trust of those who had it in me, and have had to pay the price for those things, too – and by “behave in a way I don’t condone,” I don’t mean fighting and arguing.

All those years, I’d missed my father and found it hard to forgive him for what I believed were self-esteem wounds that made me want for confidence as a youth and left me open and vulnerable to making terrible choices when I should have been leading my family. Hitting rock bottom in my own world made Dad come to life in a whole new way. In failing, I understood his plight and, just as I never wanted to harm those in my life, recognized that he didn’t either. It painted a powerful picture of what forgiveness means and how impossible it seems that God should love us, forgive us, and still seek to use us when we are utterly horrible to one another sometimes and ungrateful for the blessings we receive.

One place I served – a place Dad never made it to – was Alaska. Mount McKinley, the highest mountain in North America, was a few hours away, but most of the time was veiled by thick clouds and fog. Some say you’re only likely to get a clear view of it once in every five opportunities. When you do get that view, however, it is a sight to behold and one that is visible for hundreds of miles.

The volatile version of my father I grew up with makes me think of this mountain. Often, Dad was surrounded by storm clouds that robbed him and those around him of his true virtue; sometimes, that cloud would lift, and I would see the brilliance beneath. That was the man who showed up at my medical hearing in Oklahoma when my career appeared over before it started. It was the same guy who would bend over backward to help strangers at his own expense and even his family’s privacy, like the time one of his childhood friends was given a place to stay during hard times for months on end in the mid 1990s.

I know if my Dad were here today, he’d be proud of me, want to celebrate my successes together, communicate with me every day with incredible interest about the things I am doing in this world to make it a better place, and perhaps most importantly, affirm me and forgive me for the things I’ve done that have brought pain to others and negative consequences in my own life. Making poor choices and winding up at rock bottom helped me to understand the man I felt had disparately harmed me growing up.

It was Dad who gave me my wit and unique talents for writing and speech, and taught me:

· “Your attitude is your altitude” (Envision success)

· “The game is never over until the last man is out” (Don’t quit)

· To celebrate small victories, because you never know if you’ll have one again

· Provide learning experiences for your kids and grandkids to make them better versions of yourself with each passing generation

· Never live life on your knees or allow others to walk all over you

I made it back to my tent in Afghanistan in the dead of night near the end of September 2010 and received a stack of care packages and mail that had piled up since I left almost three weeks earlier. In that stack was one last letter to me from Dad, written 25 days before he left for Heaven, and only about two weeks before he was bedridden and unable to communicate in writing or speech.

An excerpt:

…Take your children to ballgames…Baseball teaches rules and skills. Playing the game well is only one component, understanding the game was a more important component. You learn to love the game by understanding it whether you play well or not. In fact, some who play well don’t really understand the game well or they wouldn’t make the strategic mistakes they do on the field…

We had fun at games. We had good and bad ballpark food…we sought solace sometimes… we loved each other so much at the ballpark and everywhere else too. Love you, DAD

A simple reminder of the man within, given to me after I had bid him farewell.

I did eventually wind up taking all three of my children to their first ballgame three years ago, and I thought about this letter the entire time we were there. It wasn’t quite the same as the old days sweating it out under the Texas sun, but when possible, I teach them life’s rules and skills, the lessons of success, failure, and consequence – and in doing so, am confident they will remember their father as an imperfect man with a character that wanted what was best, even if incapable of always delivering it perfectly.

Now you know why I see my sometimes vulgar, aggressive, temperamental, overly indulgent, and emotionally hurtful father the way I do. My own failures taught me to overlook his faults, because in fact they were my own faults and permanent anchors if I were to let them take full dominion over me. My best skills and the lasting encouragement of my heart came from the man who dealt me some of my deepest wounds, but he had my back to the gates of hell, and only in death have I come to know how much like him I truly am. For those who currently or would in the future seek to hold my failures against me, you condemn yourself and refute the very things you claim to believe.

Seth Keshel, MBA, is a former Army Captain of Military Intelligence and Afghanistan veteran. He is intent on living life as fully as possible, taking adventures, and finding new ways to appreciate the road less traveled in pursuit of Freedom.

Your heartrending comments hit me hard. I’ve often felt like I was the only one, with different reasons. My dad was killed in an AF crash in Canada in 61 returning to Ellington from Alaska dropping the Airborne. My mother was the abusive one. 9 years later I made my fire 3 a/c exits at Benning out of the same type a/c. I have long admired your work, you’re a driven man. Thanks for a very needed cathartic moment. Drive on Sir.

Wow Seth, I need to quit reading your emails at work. It gets me too teary eyed. Your words strike a chord in many ways. I also love your father's statement, "Son, I didn’t serve three f***ing tours in Vietnam for my son to be afraid of a bunch of stone-age, camel herding savages." Thank you for all the work you have done in this election fiasco. The fight is still on, and I'm glad you're here on our side.